Penn Museum unveils a new gallery that examines the struggles and resilience of Indigenous nations

For more than a decade, the Penn Museum has offered visitors an encyclopedic history and perspective on Native American history, with artifacts spanning from Alaska tribes to communities in the southernmost part of the continental United States.

On Saturday, the museum unveiled a new gallery showcasing the artistic, linguistic, spiritual, and revolutionary traditions of Native Americans across the country.

The Penn Museum’s "Native North America Gallery: Rooted in Resilience. Resisting Erasure" exhibit features more than 250 cultural items and art pieces.

Christopher Woods, Williams director of Penn Museum, said the new gallery builds on the institution’s expansive Native American collection while offering insights into the lives of Indigenous Americans today. It builds on a former gallery, which similarly focused on first-person narratives and consulted with Indigenous curators.

“We’re an archaeology museum, but this is really about Native American people today, and drawing on the connection between the past and the contemporary world. It’s important to show people that these are vibrant communities,” Woods said during a press preview. “Showing how strong they are, the nature of their resilience, the historical and cultural erasure, and having them speak in their own words is important.”

These works, which build on the previous exhibition, "Native American Voices: The People - Here and Now," that closed in July, offer a reframing of Native American history from four regions of the United States, including the Lenape Natives of the Delaware.

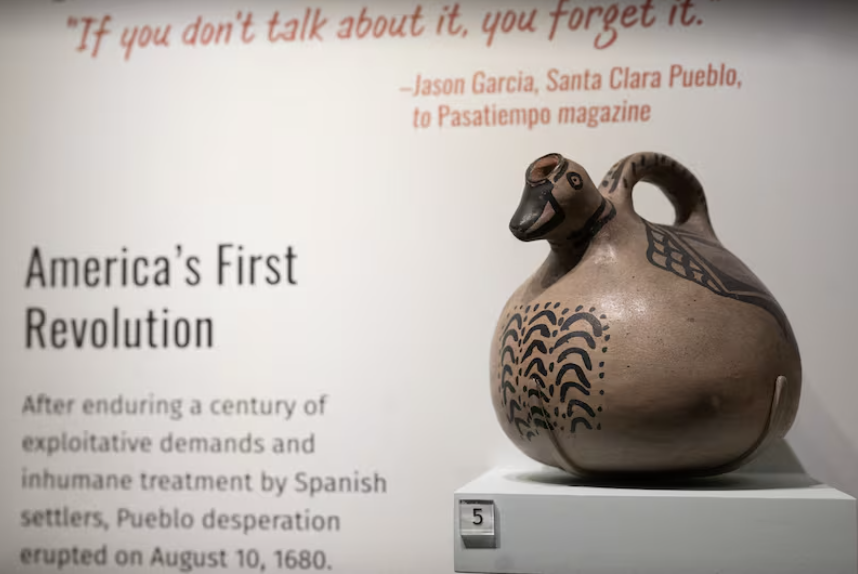

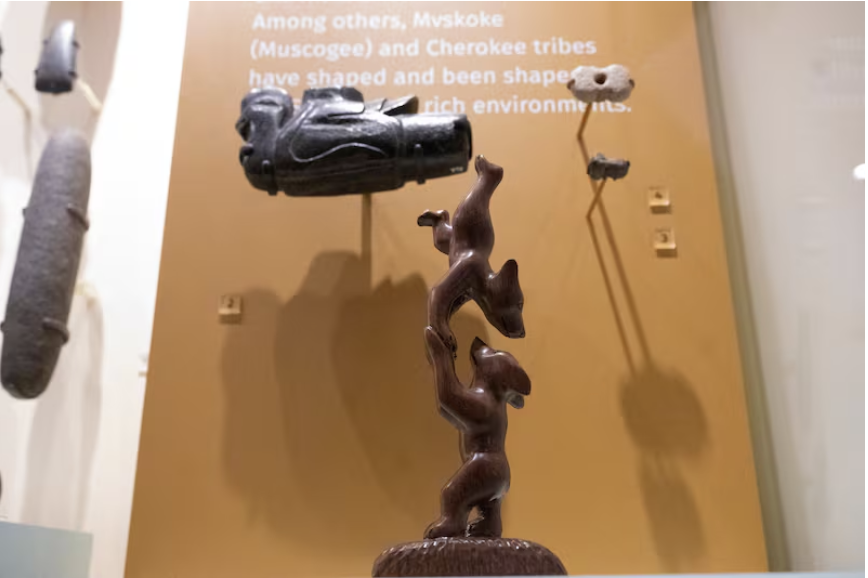

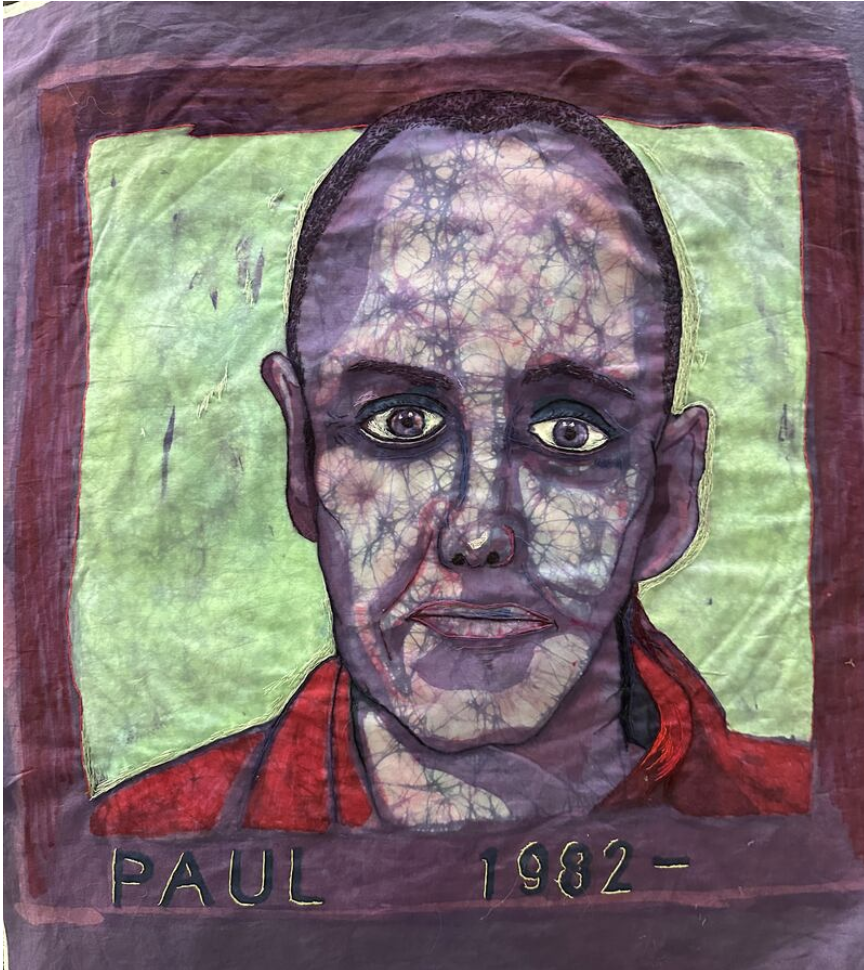

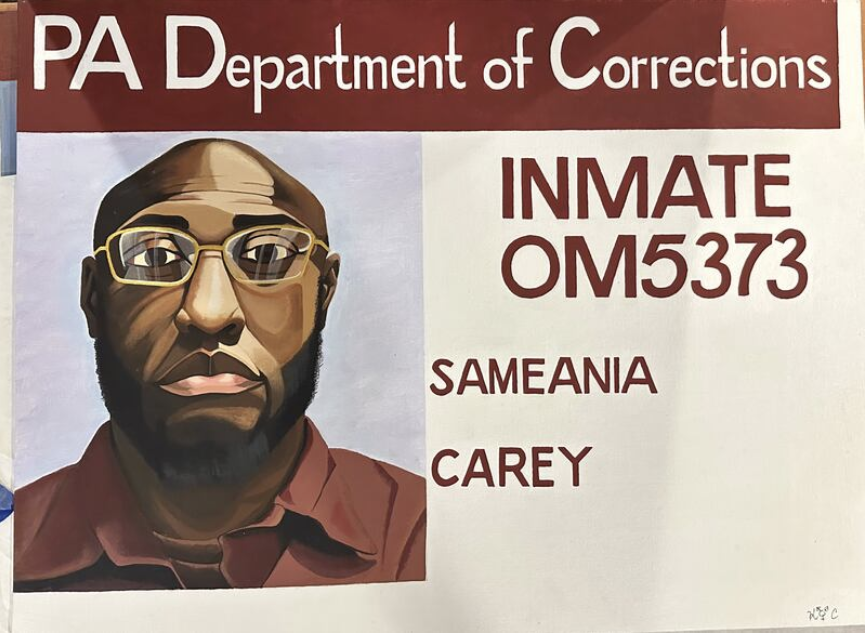

The immersive, multisensory exhibit includes a floral beadwork collar from the Northeast Lenape, a single-weave square basket from the Eastern Band Cherokee in the Southeast, a centuries-old clay ancestral mug from the Pueblo people of the Southwest, and a fringed ceremonial robe, known as a Chilkat blanket, from the Tlingit people of the Northwest.

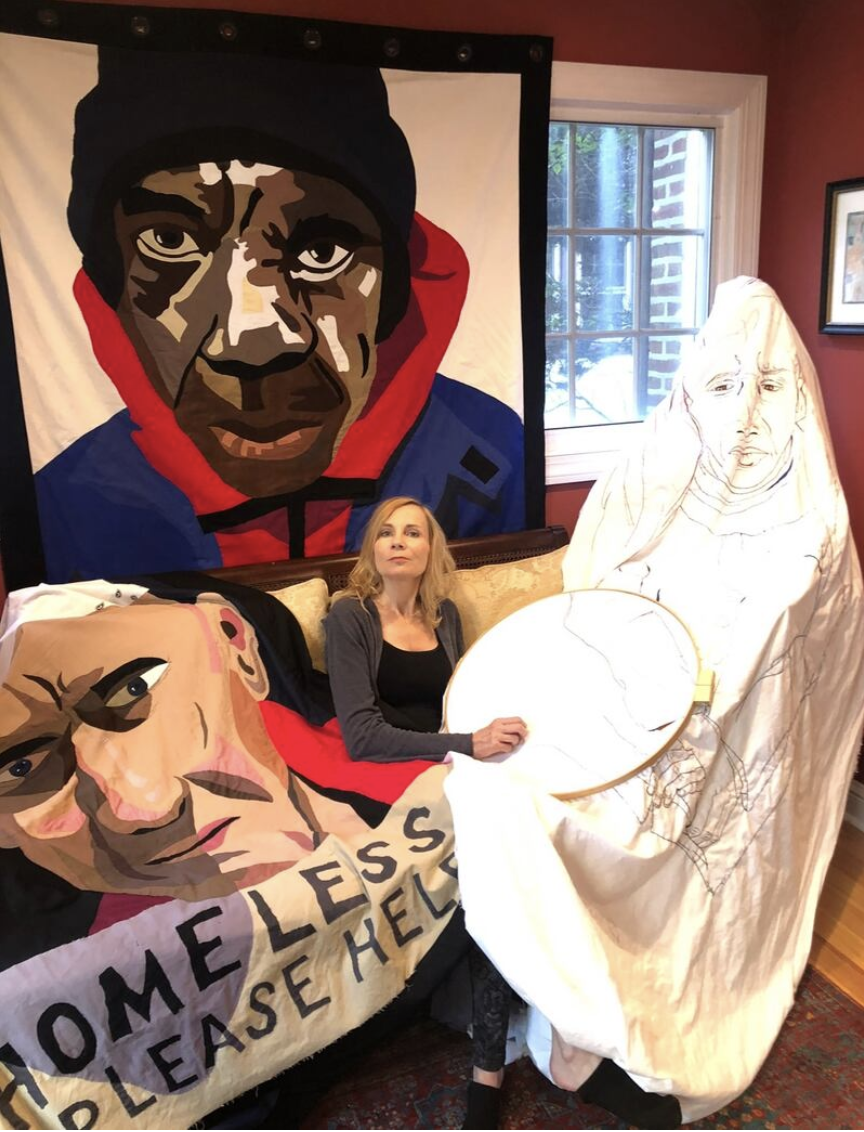

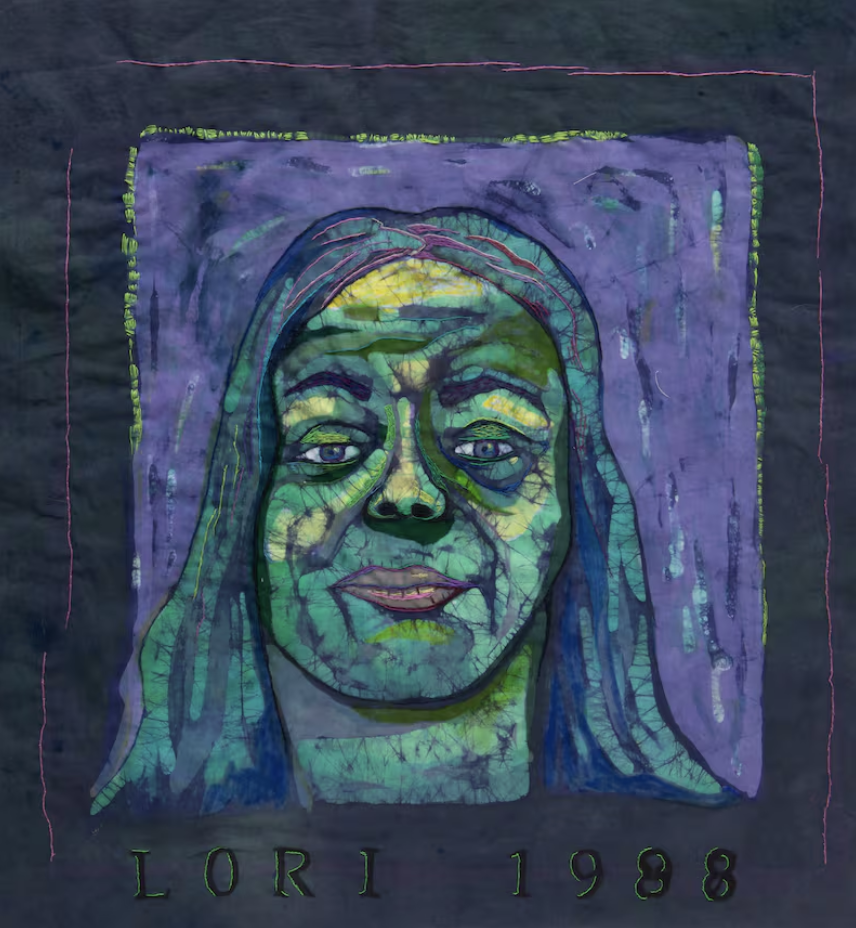

Among the oldest items on view are chipped stone tools historically used by Native Americans, which were pulled from the Penn Museum’s collections. The newest items include a woven piece that was commissioned from Cherokee mixed media sculptor Brenda Mallory.

The gallery also includes images of regions the tribal nations have inhabited, interactive displays offering insight into the formation of their cultural items, tools, and regalia, and varying stories about their traditions, challenges, and resilience before and after European contact.

Alongside co-curators Lucy Fowler Williams and Megan Kassabaum, this comprehensive gallery was developed by cultural educators, archaeologists, and historians who are direct descendants and members of the tribal nations featured in the exhibit.

Among the eight Indigenous consultant curators, who served as narrative guides, were Jeremy Johnson, cultural education director of the Delaware Tribe of Indians, RaeLynn Butler, secretary of culture and humanities of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and Christopher Lewis, cultural specialist of the Zuni Pueblo.

The consulting curators assisted in creating the narrative flow of the gallery and worked with the Penn Museum to recover lost history and study their ancestors’ practices. They also contributed their own art and cultural items to the gallery.

Upon seeing the exhibition for the first time on Thursday, Johnson said it was an “emotional moment.”

“It was overwhelming,” he said. “It’s not just a room with a bunch of paintings or drawings. These are actual people I lived with, know, and are related to. I can tell you about every person here. Being able to give our tribal citizens, considering everyone is a relative, a voice was really emotional. We’ve always been seen as relics of the past.”

Kassabaum said the concept of the exhibit began four years ago, but many of the gallery’s elements were shaped by the consulting curators, who willingly shared their stories and welcomed Kassabaum and others into their communities.

Kassabaum and other Penn Museum consultants traveled to Oklahoma to spend a week with members of the Delaware Tribe. They brought back four items, including the floral beaded collar, and let their protectors relay how they were made.

Those kinds of connections can’t be made without the help of the consulting curators, Kassabaum said.

“These aren’t my stories and they’re not my experiences,” he said. “I have not experienced any of the trauma of these communities. I have not experienced the joy of these communities, and everything people have been willing to share with us has been incredible. … No matter how giddy or passionate I am about anthropology and archaeology, I can’t bring the same thing to the gallery. It was totally essential.”

Unlike other exhibitions sprawled throughout the country, Johnson said Penn’s inclusion of him and his Native “relatives” was based in good faith rather than historical or cultural exploitation.

“We know certain art museums have been problematic in the past, and are still doing that work,” Johnson said. “But I feel this is the first time we were asked in the right way. It was in the spirit of an actual collaboration, instead of asking for items to display, and that’s it. This was a good process, and we hope it stands as a model for future exhibits.”

The opening ceremony of the Native North America Gallery kicked off with remarks from Johnson and the other Indigenous consulting curators.

Their remarks were followed by traditional dance, songs, and storytelling by New Mexico’s Tewa Dancers. There was also an artist talk by Holly Wilson of the Delaware Nation, curatorial presentations led by Johnson and Joseph Aguilar of the San Ildefonso Pueblo, and a series of family workshops.

The gallery, which is now on display, is available for online and in-person viewing.

Visitors can reserve guided, in-person tours on select days. Tickets are priced at $26 for members and $30 for general admission. For more information, visit penn.museum.

– The Philadelphia Inquirer